|

Elizabethan dream, in which Julius Caesar and

Arviragus characteristically figure.78

A second pharos seems to have stood opposite to the

one just described, three-quarters of a mile away, on a spot now

covered by the Drop Redoubt.79 To the earlier

antiquaries this pharos was better known than its neighbour on

the Castle Hill. Indeed, Leland, Lambarde and Camden mention the

former and ignore the latter. Old views of Dover show that as

late as the end of the seventeenth century this tower stood high

above ground, a prominent mark on the bare Western Heights. |

|

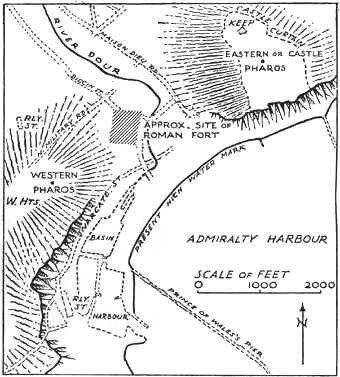

FIG. 11 SKETCH MAP OF DOVER, SHOWING THE

SITES OF THE CASTLE PHAROS, THE WESTERN PHAROS, AND

APPROXIMATELY THE ROMAN FORT (Reproduced from Arch.Journ.

lxxxvi, 30)

|

The Canterbury antiquary, Thomas

Twyne, told Camden that in his youth he had seen it nearly

perfect, and that it was a pharos. He was probably right. It

must at least have served as a seamark; and it is but a slight

step further to imagine that Roman Dover was flanked by twin

lights which would serve not merely to ‘bracket’ the harbour

but would form a distinctive feature amongst the coastwise

signals. By the first half of the eighteenth century the western

tower had fallen into an advanced state of decay. It was then

known alternatively as the Bredenstone or the Devil’s Drop,

and here, from the middle of the seventeenth century onwards,

the |

|

Lords Warden of the Cinque Ports were sworn

in. After further vicissitudes the foundation of it was buried,

in 1861, in the present redoubt, in which a small and formless

fragment of it is still

78 For the pharos

see Leland, vii, 128; Stukeley, Itim. (ed. i), p. 121,

the first attempt at a real survey; Wheeler, Arch. Journ. lxxxvi,

29, a full account. On ancient phari generally, see H. Thiersch,

Pharos (Leipzig, Teubner, 1909). For the church—often,

but absurdly, ascribed to the Roman period—see Gilbert Scott, Arch.

Cant. v, 1—18; Micklethwaite, Arch. Journ. liii,

327; Baldwin Brown, Arts in Early England, ii, 292, 308.

Canon Puckle’s Church and Fortress of Dover Castle (Oxford,

1864) contains useful details, but is written with little

knowledge of Roman history or archaeology. The author thinks

that British Christians built the church about the end of the

Diocletian persecution, ‘when their weakened masters were on

the point of abandoning the colony.’ This ignores the 100

years which intervened between Diocletian and the withdrawal of

the Romans from Britain; and it also mistakes the relations of

Romans and Britons at the time. Cf. Peck in Brit. Arch.

Assoc. N.S. xx, 24B; and Haverfield in Brit. Acad. Suppl.

Papers, ii, 1914, p. 3.

79 For a

full account of the history of this ‘ pharos’ since the

sixteenth century, see Wheeler, Arch. Journ. lxxxvi, 40. |