|

Aspects of Kentish Local

History

|

Otford & District Archaeological Group (ODAG)

The

Romano-British Cremation Cemetery at Frog Farm, Otford, Kent, in the context

of contemporary funerary practices in South-East England by Clifford P. Ward

1990

Romano-British Funerary

Practices in the 1st and 2nd Centuries A.D.

Hominem mortuum in urbe ne

sepelito neve uxito

Thou shalt not bury or burn a dead man within a city

-

regulation of the Twelve Tables

reinacted by

Antoninus Pius (138 - 161).

As a result of the

regulation of the Twelve Tables the vast majority of citizens of the Roman

Empire were buried outside the settlements to which they belonged, often grouped

along the roads leading from them, where their monuments would recall the dead

to the minds of the living (Collingwood & Richmond 1969). The grandiose tombs of

the environs of Rome were paralleled in many towns and cities of the Empire, and

on a reduced scale in the vicinity of lesser settlements throughout the Roman

World, including Britain. In this tradition, a cemetery was established on the

ancient road which runs along the lower slopes of the North Downs, now known as

the Pilgrims Way, some 300 yards (275 metres) east-south-east of a

Romano-British settlement, and 1250 yards (1150 metres) from the nearest

definitely located Roman Villa, east of the River Darent, with another 500 yards

(450 metres) postulated to the south. The settlement flourished throughout the

Roman period, and may well have acted as a market for the surrounding rural

area, without developing into a town, the inference being that administration

was carried out from the town of Durobrivae (Rochester) some sixteen miles

distant along the Pilgrims Way (Rivet 1964). It is likely that Otford

supplemented the other minor settlements in the vicinity as a distribution

centre as well as acting as a minor centre for iron-working (Pyke forthcoming)

and pottery production of Patchgrove wares (Breen 1987).

There appears to have been a fundamental difference in attitude towards the

after-life between the Romans and Celts, the former looking without much

enthusiasm on the prospect, at least until the 2nd. century A.D., with 'sit tibi

terra levis’ (let the earth lie lightly upon you) being the recurrent theme. An

equally pessimistic epitaph on a Wroxeter tombstone

proclaimed, "drink while your star gives you time for life", and that on a

memorial stone to a thirteen year-old York girl refers to 'the meagre ashes and

the shade, empty semblance of the body seeking the manes who dwell in Acheron,

the river of woe (Henig 1984).

The care shown by the Romans in their burial practices was to ensure that the

requisite minimum covering of earth prevented the deceased from haunting the

living, the fear of ghosts being to the forefront of men's minds (MacDonald

1977). Toynbee considered that the denials of survival of the Epicurean and

Stoic systems were not universally accepted by the Roman people, and that human

life was not invariably regarded as merely "an interlude of being between

nothingness and nothingness", there being some conviction of a continuing soul

whereby the living and dead can affect each other mutually. This more optimistic

approach gained momentum from the spread of eastern-cults, with the ultimate

belief in the resurrection of the body inspired by Christianity, which found

official favour in the early fourth century (Toynbee 1971).

The Celts on the other hand, had a long-held "strong belief in a positive and

tangible afterlife where the accoutrements of earthly life will be required and

the terrestrial status retained" (Green 1986).

The Roman last rites in the Republican period comprised both inhumation and

cremation (Toynbee 1971), but from the early Imperial age that of cremation

became almost exclusively used, until a growing belief in the survival of the

body pervaded pagan belief, closely followed by Christianity which gained

credence throughout the Empire, especially after the official toleration,

granted by Constantine in the Edict of Milan in A.D.313 (Somerset Fry 1984).

In the pre-conquest Iron Age in Britain, there was doubtless ceremony

attendant on death, as in the preceding Bronze and Stone ages, but,

comparatively little tangible evidence remains. Caesar comments in Book VI of de

bello Gallico on the opulence surrounding Gallic aristocratic funerary rites,

but makes no reference to ultimate disposal of the remains. Of course, regional

and or religious belief variation may have occurred to some degree, but it is

likely that, in a tribal society as Iron Age Britain, uniformity would be found

within the tribal spheres of influence, and it is likely that many of the ruling

aristocracies had links in a common ancestry; their religious beliefs are likely

to have been maintained, although the requirements of social custom may have

been as strong a factor at the time in regulating the funerary rites (Henig

1984), while the act of passing into the After-world, an occurrence familiar to

everyone involved in communal life, must have had considerable influence on the

thought-processes and superstitions of the community (Kendall 1982). Darvill

identified a Core Zone, comprising the lower Thames valley, including Kent,

Surrey, Sussex, London, Essex, Hertfordshire, and parts of Buckinghamshire and

north Hampshire which by the mid-1st century B.C. enjoyed a superior economy and

close links with the continent, and, in common with the rest of the area, in

Kent cremation seems to have been fairly well-established from c. 40 B.C. (Darvill

1987) where cremation cemeteries, although not exclusive, are ubiquitous in

utilising small pits to hold ashes placed in urns. These are known from their

type-sites of Aylesford and Swarling. Often the ashes were placed in wooden

buckets, accompanied by rich grave goods. Other graves contained from many to

few, or no, grave goods, and are considered to be of Belgic tradition.

There is a discernible trend in the later Iron Age towards inhumation in

Sussex, which, separated by the relatively uninhabited Weald, could develop a

separate non-Belgic tradition (Bedwin 1978). The development of the wealden iron

industry in the Roman period has not to date provided any tangible evidence of

burial rites (Money 1990), but cremation seems to have been current in the

earlier phase of Roman Chichester (Down 1978).

Recent researches indicate that there was a major development towards a more

settled form of land-ownership in the late pre-Roman Iron Age in lowland

Britain, and that the Roman Conquest accelerated rather than initiated the

process (Salway 1988), it being generally accepted that there was a considerable

increase in the numbers of country dwellers in the Roman period (Bird 1987).

Investigations suggest that in Iron Age society only a minute proportion of the

population was accorded burial rites, probably the elite (Green 1986), but after

the conquest it appears that both high and low were afforded burial or

cremation, though with differing elaboration.

The imposition of Roman rule in the south of England in A.D.43 probably had

little impact on the everyday lives of the ordinary people, and beyond the final

crushing of the British druidic theocracy in Anglesey in A.D.60 by Suetonius

Paullinus (Frere 1973) possibly in response to its human sacrificial practices,

barbaric, even by Roman standards, or, as hinted by Pliny the elder, through

their morale-lowering gloomy prophesies (Somerset Fry 1984), their religious

beliefs were probably allowed to continue unhindered, with a gradual syncretism

of Roman and Celtic dieties (Clayton 1980). The part played by the Druids in

Celtic society is still unclear, as their ritual and theology was unwritten, but

they probably were socially, rather than politically, very powerful. They appear

to have had their origins in Britain, and after the Anglesey rout they do not

reappear in Roman Britain. However, they were active in the Gaulish uprising of

A.D. 69-70, and druidic prophesies against the emperors are recorded in the

third century. They also continued to wield influence in Ireland as magicians

and soothsayers.

The Roman authorities were in the main extremely tolerant towards foreign

religions, provided they were not redolent of political conspiracy or repugnant

rites, and they tended to conflate local deities with the Roman pantheon (Salway

1988). Hence as a funerary rite cremation continued to be practised in a more or

less traditional manner, and first and second century A.D. examples abound in

districts where settlement was effected or continued.

With a few notable exceptions e.g. St. Pancras, Chichester, and Lankhills,

Winchester, relatively few cremation cemeteries have been excavated using modern

techniques, and no direct parallels to Otford have been traced. That at Ospringe,

which served a still unlocated but substantial nearby settlement, bears many

similarities, although it is considerably larger and has inhumations as well as

cremations (Whiting et al 1931). Some cemeteries were discovered long before

adequate recording techniques were invented, and tantalising glimpses alone

remain as of "a Roman cemetery discovered upon East Hill, near Dartford

A.D.1792, in which have been found great numbers of urns, intermingled with

stone and wood coffins, lachrymatories etc. together with the square pits in

which the bodies were burned" (Dunkin 1844). Also near Dartford, another

depressing note records that at new gravel pits at Joyce Green, "workmen found

several Roman urn burials of the ordinary kind, consisting of small groups of

urns here and there" (Payne 1897).

Other opportunities have been lost even recently, such as the presumed

cremation cemetery adjacent to Canterbury Castle where there were "vague reports

of further cremations" seen during construction at the Gas Works in the 1950s

(Bennett et al 1982).

A number of deep shaft graves of Iron Age date from South-East England

suggest a multiple, possibly family, use, and shaft burials continue into the

Roman period. There is much speculation as to the religious significance of

these shafts, many of which are classed as 'ritual pits', apparently linking the

world of the living with the underworld, and suggestive of propitiation of

chthonic deities. These are predominantly, but not wholly, found in areas of

Belgic influence, and some, such as South Cadbury, where a young man was buried

head-down in a pit associated with alterations to the Iron Age defences, suggest

a dedicatory sacrifice (L. Alcock 1972).

An extremely well-constructed rectangular oak shaft, 12ft. in depth was

discovered during railway building at Bekesbourne Hill, near Canterbury, in 1858

at a depth of 13ft. below the modern ground level. It was built of nicely

mortised and tied oak baulks and had an internal diameter of 3ft. 3ins. (l

metre). At the bottom was a large (?) quern stone on which was placed a circle

of horse teeth. Above this were five urns apparently covered with fabric. These

in turn were covered by a layer of flints on which stood a further urn again

covered by flints. The urns almost certainly contained cremated bones. The

structure was roofed with more oak beams and was in remarkably good condition,

but was destroyed largely due to the efforts of treasure-seeking navvies (Brent

1859).

A recently discovered shaft at Deal, Kent, contained a chalk figurine

comprising a 'Celtic' head surmounting a dressed block. Associated pottery dates

this to the first or second century A.D. and this is a pointer to the idea of

communication with the underworld powers (Green 1986). Many shafts contained

animal bones, especially of dogs, sometimes with human remains, and the 225ft.

deep well at Findon, Sussex, contained inter alia the remains of a horse

(personal observation). So-called ritual shafts in or near cemeteries in

South-eastern England with rich assemblages of pottery, animal bones and other

artefacts, but without human remains, taken as depositories for offerings, have

been found (Black 1987).

At Keston, Kent, a shaft l6ft. deep and 11ft, wide was excavated and found to

contain cremated remains of two dogs together with pottery described as

indeterminate but tentatively ascribed to the 3rd.-4th. Century A.D. (Piercy Fox

1968, Jessup 1970 ), while a well at Staines, Middx., contained parts of no

fewer than 17 dog skeletons (Bird 1987).

Graves, as such, from the Iron Age are very uncommon, and it appears that if

dug, they were so shallow as not to have survived later disturbances of the

ground. A further possibility is that there was some form of above-ground burial

chamber or charnal house, where bodies were either exposed, or, more likely,

laid to rest in wooden structures for at least a limited period of time (Black

1987). The ubiquity of the so-called 'four post' structures in Iron Age

settlement sites gives weight to such a hypothesis, and the use by the Maoris of

New Zealand of such four-post bases for cantilevered rectangular storage huts

illustrates the practicality of such (personal observation).

This would allow the veneration of ancestors by the living, a likely attitude

among people who are believed to have placed great store on qualities which

could be inherited, even from enemies vanquished in battle, through exposure of

severed heads in their dwellings (Delaney 1986). The eventual disposal of the

skeletons seems to have been of lesser consequence, as disarticulated bones have

been recovered from rubbish pits (L&R Adkins 1983).

Attempts have been made to identify specifically Roman military cemeteries

but this has been largely unsuccessful despite the considerable number of

military tombstones known especially from northern Britain, leading to the

conclusion that after the conquest the soldiery played a part in developing

local community traditions. The early garrisons followed their own ethnic or

Roman customs, but gradually the military and civilian traditions mingled and

‘the early Roman style of cremation burial, usually in a pot with an assortment

of Romanised goods as grave furnishings, became general for most of the

Romanised population’ (Jones 1984).

It has been established that at a number of sites in Southern England

cremation was practised on a fairly large scale, with structures identified as

collective crematoria, as at Colchester, Essex, (Hull 1958), and outside

Verulamium (Davey 1935), where confined areas of burning some 1.8/2.4m by

0.7/0.9m (5ft. 10ins/6ft. l0ins. by 2ft 3ins./3ft.) in extent, suitable in size

for cremation of a body, were located within cemeteries. Toynbee, quoting Roman

authors, postulates that the cremation took place either at the place of burial,

or at a special crematorium. The wood-pyre was rectangular and the body placed

upon it with opened eyes. Various gifts and possessions were added, and

sometimes even pet animals were killed as companions to the afterlife. After the

mourners had called the deceased by name a final time, the pyre was kindled with

torches. The ashes were ultimately drenched with wine, and the ashes and bones

were subsequently collected by the relatives and placed within receptacles which

varied with the wealth of the family from marble ash-chests or caskets, precious

metal vases, to lead, glass or earthenware vessels (Toynbee 1971).

It has been suggested that wine may have had some particular significance in

the funerary ritual, and many burials containing amphorae have been found in

Roman and pre-Roman graves and that the presence of wine may have transcended

ostentation or refreshment of the deceased (Salway 1988). At Otford, 36% of the

graves contained flagons or bottles, had cups, while 17½% had both (see below).

After the funeral, relatives underwent a purification rite by fire and water,

cleansing ceremonies were held at the deceased's house and a funerary feast was

held at the grave in honour of the dead. Later, offerings were made at the grave

including a libation to the Manes, and throughout the year funerary meals were

partaken as at the deceased's birthday and festivals of the dead (Toynbee 1971).

As Alcock observes 'the surviving evidence, in fact, suggests that in Britain

the toleration which Romans showed towards religious beliefs extended equally to

rites relating to the formal disposal of the dead. Celtic religious ideas are

seen to continue throughout the Roman period even after the adoption of

Christianity, and personal choice was permitted in both religious and burial

practices (Alcock 1980). Thus Southern Britain rapidly settled down to Roman

rule, and rural dwellers undoubtedly continued to live in much the same way as

hitherto, with a nominal respect for Rome's gods and the 'dull divinised

emperors', whilst perpetuating their veneration for the old proven gods of their

own tradition (Ross 1967).

The tradition of cremation apparently gained popularity to the point of

virtual exclusivity in the first century A.D., and remained predominant in

Britain until the 3rd century. The earliest recorded Romano-British inhumation

cemetery identified so far was found at Chester, dated to the second half of the

2nd century being closed c 200 A.D. (Collingwood & Richmond 1969).

A further possible reason for the changes from cremation to inhumation, or

vice versa, is cultural rather than religious, as when, within the last 100

years, British funerary practices have changed from 100% inhumation to 50%

cremation (Drewitt 1988).

The polytheism of the Roman Empire developed through absorption of the

religious beliefs of the many peoples who were incorporated into it. With the

notable exceptions of Druidism, Judaism and Christianity, it appears to have

tolerated most of the religions it encountered, and in many instances linked the

local gods with the Roman pantheon, the interpretatio Romana, thus, Jupiter, the

chief Roman god, was linked with the Greek Zeus, and Juno the chief Roman

goddess, was linked with her Greek counterpart Hera.

In Britain, inscriptions have linked Minerva with the Celtic goddess Sul (Sulis)

at the Bath geothermal springs, also with the Brigantian tribal goddess

Brigantia, and Mars with Medocuis, apparently an East Anglian British deity,

(Somerset Fry 1984), elsewhere the equation appears as Mars Lenus, and Mars

Anextiomarus (Frere 1973), and numerous other correlations have been identified.

In addition to the indigenous Celtic religions, mystical eastern religions

were transmitted throughout the empire by military personnel, traders and

possibly slaves, which are represented in Britain as in other provinces by

temples and altars, statuary and regalia e.g. at Walbrook, London and

Carrewburgh, although the rituals of some were eliminated by the early church as

parodying the death and resurrection of Christ.

The varied nature of grave-goods (see below) indicates a conscious attempt to

equip the spirit of the deceased for its journey into the underworld, possibly

after a period of confinement to the grave, and whereas some objects of

considerable intrinsic value were interred or burnt on the pyre to judge from

extant remains, the possibility cannot be excluded that the belief was less than

wholehearted, at least in some instances.

Among references to the superstitious beliefs in Roman society in the works

of classical authors Alcock cites Heroditus, where Perandius' wife complained

from the otherworld that she was cold because her clothes had not been burned

with her (History v.27) (Alcock 1980).

In a late first century grave at Lankhills cemetery, Winchester, the remains

of a meal including a young pig and poultry were recovered, and evidence among

the interments of some weird and outlandish funerary ritual, including

decapitation, suggested to ease entry to the otherworld (Green 1986). It has not

been possible to identify any traces of food or drink in the vessels

accompanying the urns at Otford, but such could well have been destroyed by the

soil conditions, although some instances of vessels having been inverted at

deposition, and one (Group 45) with three vessels standing one within the other,

suggest that these, at least, were empty. On the other hand, an early second

century cremation at Canterbury castle included a samian dish which contained

the remains of a small bird (Bennett et al 1982).

It is clear from both surviving inscriptions and the writings of Roman

authors that the religions of the Roman world were abounding in superstition,

and that burial practices were intended to ensure that the spirit of the dead

person did not return to haunt the living (Alcock 1980), a sentiment expressed

by Ovid. The numerous references to the symbolic breaking of grave goods, a

practice traced back as far as the La Tene period (Green 1986), indicate that

the symbolism continued into Roman times, and various authors (e.g. Jessup 1955

and Alcock 1980) point to the Celtic and Roman belief in 'killing the life

spirit' before placing objects in the grave or on the funeral pyre. It is also

possible that sometimes it may have been intended to discourage or prevent

re-use after ritual dedication (Salway 1988). At Portslade, Sussex, associated

with one of the cremation groups in a Roman cemetery, the skull of a

sub-adult/hornless sheep was unearthed, considered to be intended either as

nourishment for the deceased or as a ritual deposit to facilitate entry to the

netherworld by the deceased (Gilkes 1988). Vegetable matter seldom survives in

cremation burials but 'walnut or filbert shells' were noted with cremations in

the wet conditions within the Bekesbourne shaft (Brent 1859).

Black draws attention to an apparent development in the scale of provision of

eating and drinking vessels, and suggests that 'the generous provision of

feasting equipment in Welyn-type burials and the lavish multiplication of pots

in first century Romano-British cremations seems to attest a strong belief in

the need for sustenance within the grave. Out of this there seems to emerge

something like a standard set of vessels : cup/beaker, flask/flagon, and

bowl/jar/plate. He goes on to point out that vessels are rarely found after the

mid-fourth century, and postulates that the burial of pots and other containers

appears to have become a customary rather than a religious duty by then, perhaps

earlier (Black 1987). This would tend to reinforce the suggested influence of

Christianity by the fourth century on the inhabitants of Roman Britain, with

rejection of continued earthly needs associated with the doctrine of

resurrection.

A possible analogy in modern Chinese (Hong Kong) society is that paper models

of wealth symbols, e.g. houses, cars, and "Hell bank-notes" are burned on

funeral 'pyres' (minus the body) to support the deceased in the afterlife

without detriment to the wealth of the living (personal observation). An

intriguing possibility arises from the foregoing, that a somewhat similar view

was abroad in Roman Otford, suggested by the inclusion of imperfect vessels as

grave-goods (see below).

Recent studies have concluded that there is significance in the alignment of

inhumation graves (Kendall 1982) and it is equally possible that there was

relevance to the community in the arrangement of ancillary pots and objects

placed with urns. At the St. Pancras cemetery at Chichester the excavators noted

three instances where the vessels were ‘arranged in a semi-circle with a flagon

or dish opposite and the bones scattered between’ (Down & Rule 1971). However,

at Otford the plough damage and incomplete investigation of the cemetery

diminish the chances of establishing a reliable or even recognisable pattern.

At Otford there have been no identifiable graves of infants or small

children, although mortality of such is likely to have been fairly high during

the Roman, as in earlier and later, periods. Numerous burials of infants within

villas e.g. Lullingstone (Meates 1979) farms e.g. Sedgebrook, Plaxtol (Bishop

1990), and temples e.g. Springhead (Penn 1967, Jessup 1970), to quote local

examples, are generally regarded as foundation deposits, and likely to have been

available products of infant mortality rather than human sacrifices (Henig

1984).

At King's Wood, Sanderstead, a cemetery was discovered just outside the

entrance to a small farming community extant in the first and second centuries.

It contained five cremation interments of babies and small children and appears

to be exclusive to the young, with a separate cemetery for adults further away

(Little 1961). An excavation trench at Canterbury castle yielded a late first to

early second century cremation group which proved, upon analysis of the bones in

the urn, to be the remains of both a 4/5 year-old child and a 'not elderly'

adult (Bennett et al 1986). A group at St. Pancras with 8 vessels including 2

flagons contained both an iron knife and a baby's feeding bottle, suggesting the

presence of an adult and a child (Down & Rule 1971).

That not all infants were accorded the same burial rites as adults is indicated

by a baby who apparently died at or around birth and was buried in the upper

fill of a rubbish pit at Bullock Down, Sussex (Drewett 1988). The reasons for

this unceremonious concealment must remain a matter for speculation.

In a fourth century context at Springhead the excavator interpreted a small

flint-built structure as a mausoleum, having a young child inhumated in its

chalk floor. Adjacent to this he tentatively identified 'a longish tiled feature

(some 7ft. by 2ft.) as a platform for conducting cremations', there being

extensive cracking through heat visible and a number of infant burials and

cremations in proximity. Other interpretations are possible, however, as there

are traces of industrial occupation in the immediate vicinity. A significant

general comment on Springhead is that no adult burial has been found in the

town, which suggests that rules and the boundaries of the town were still being

observed at a late date (Penn 1961).

A possible significance is suggested for the placing of shoes in relation to

the cremation urn, akin to that postulated for orientation of inhumations in

cemeteries (Black 1987); at Otford one example (group 34) was noted where a

quantity of badly corroded hob-nails was situated to the north of the urn. A

logical explanation for the presence of footwear (sandals and boots being noted)

is that they were intended to aid the deceased to walk to the underworld. It has

been suggested that in some instances only a few nails were placed in tombs as a

symbolic gesture. A pair of purple shoes was associated with a rich cremation

grave at Springhead (Henig 1984), while at Cirencester a furnace and over 2000

hob-nails were found within a building inside a cemetery conjuring up visions of

a 'dedicated' industry (Salway 1988).

Otford produced a few items which may point to a lessening in belief in, or

requirement for, grave-goods even by the mid-second century, although an

alternative explanation, that of poverty, is tenable. The creamware flagon

(group 72) was undoubtedly a kiln waster, having cracked and distorted during

firing to the extent that it could not have held a liquid. It is conceivable

that the crack could have been filled e.g. with clay as a temporary expedient,

but it remains an extremely sub-standard piece. The St. Pancras cemetery

produced 'large numbers of vessels with burials (which) were wasters, and this

could be another example of using a "killed" object for funerary purposes' (Down

& Rule 1971). A samian plate (Dr 31) from Otford (group 31) had been broken and

mended by means of lead rivets, a not unusual repair to samian plates, prior to

its deposition. The significance, if any, of the plate in its repaired state is

not possible to assess, as it is equally likely to have been the

favourite/personal crock of the deceased as to have been placed in the grave for

any other reason. Another samian item, a cup (form Dr 33) from nearby (group 70

) was discovered broken in situ, but on restoration was found to have a piece

missing from its rim, and from its position it is likely that this vessel was

also imperfect when buried.

As mentioned above, the supply of libations to the grave both inhumation and

cremation was a part of post-funerary ritual, and in many places throughout the

Roman empire, including Britain, a pipe was constructed to permit the ingress of

food or wine to the grave itself. Lead pipes were sometimes used for this

purpose, as at Caerleon (figure lb), while at Chichester a pipe was constructed

from tiles - imbrices (Down & Rule 1971).

The high incidence of flagons with interments has been noted, and a number

have had their tops missing. It is known that at Ostia flagons were deliberately

left with their necks proud of the ground to receive libations, and a similar

suggestion is made for some at Chichester (Down & Rule 1971) although this does

not appear to be the case either at Ospringe (Whiting et al 1931) or at Otford,

where a high proportion of flagons have retained their upper extremities.

According to Pliny the Elder (Naturalis historiae xxxv) the majority of

mankind employs earthenware receptacles for this purpose i.e. burial, and

pottery kitchen jars were the most ideal and cheapest containers for cremated

bones and ashes, but other vessels were also used: glass, wood, metal especially

lead, and stone (de la Bedoyere 1989). Indications of wooden boxes or caskets

are common and were found at Otford, Ospringe and St. Pancras, One such, from

Skeleton Green, Braughing, Hertfordshire, is illustrated (figure la). Ospringe

and St. Pancras both provided evidence of glass vessels, unlike Otford, but the

last-named may have contained at least one lead coffin (see below). Most lead

coffins or ash-chests were rectangular, but a cylindrical one containing the

remains of a little girl was discovered at York (Fig. 1c).

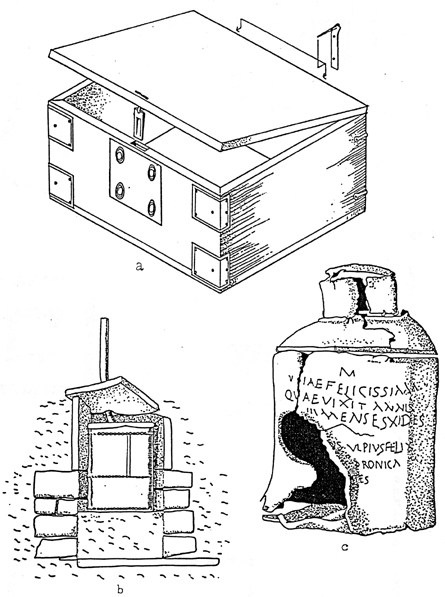

Figure 1 a) Reconstruction

of wooden casket having metal fittings and dating from the mid-second century.

Width c30cm.

From a cremation burial at Braughing, Herts, b) Pipe burial with a lead

canister in a tiled cist from which a lead pipe led to

the ground surface. Caerleon. c) Lead canister urn with remains of child and

inscription. York. (after de la Bedoyere 1989).

Pottery lamps

were provided in numerous graves, presumably to either illumine the deceased

during a sojourn in the grave or on the journey to the underworld. Although

present in significant numbers at St. Pancras (36) they do not occur at

either Ospringe or Otford.

Jewellery is found in only a

small minority of graves, and Otford is no exception, with only three groups

providing any traces. Perhaps significantly, two out of these were not

furnished with any ancillary vessels.

It is clear from the

writings of Roman authors that the Gauls, who were Celts and closely linked

to the British of southern England, had very strong belief in reincarnation,

and Julius Caesar commented that the Druids wished to convince men that

their souls do not perish, but go from one body to another when they die (de

bello Gallico vi), to the extent that they regarded death as unimportant,

the Gauls believing that men's souls are immortal and they return to life

after a prescribed number of years, with the soul entering another physical

body (Diodorus Siculus v 28).

Black suggests that Caesar's

comment on the similarity of the customs of the inhabitants of Cantium to

those of Gaul may be taken as a guide to the situation in South-east England

in the mid-first century B.C., by which time cremation seems to have been

the norm. However, his suggestion, following Whimster (Whimster 1981), that

insecurity resulting from Caesar's campaigns may have influenced the change

towards cremation (Black 1987), is only one of a number of possible reasons

for the practice, not the least plausible being changes in theology of the

Celts of Gaul and Br tain. As one authority commented, we actually know less

about the religion of the pagan Celts than certain scholars, past and

present, would have us believe’ (Ross 1967). This is due partly to the

subsequent authority of the Christian church, and partly to the ubiquitous

practice among the pagan Celts of instruction by symbols and enigmas, or

dark allegories, by ancient songs and maxims, orally delivered and in

private, by which they deemed it unlawful to reduce into writing, or to

communicate to any but their own order (Meyrick 1848).

Thus the destruction of the Druidic priesthood caused the loss of

their philosophical traditions, which Ross concluded to have been 'little

different from the priest/shamans of the entire barbarian and later pagan

world concerned with shape-shifting and primitive magic, controlling ritual

and propitiating the treacherous gods with sacrifice’ (Ross 1967).

Pomponius Mela,

writing cA.D.43 records one such maxim, a triad, apparently a form of Celtic

catechism:

"To act bravely in war

That souls are immortal

And that there is another life after death"

-De Situ Orbis.

A similar triad is preserved in the writings of the third

century Greek author Diogenes Laertius:

"To worship the Gods

To do no evil

And to exercise fortitude" (Meyrick 1848).

Doubtless many superstitions connected with the natural world are

pre-Christian survivals, and some, such as providing a symbolic coin or

coins in a burial, are directly descended from Roman practices relating to

payment to Charon for the journey by boat to the underworld, and to earlier

Greek and Egyptian beliefs. Black, commenting on the low percentage of

Romano-British graves containing coins (2-6%) and even lower of

cremations (where survival of coins is more doubtful), suggests that the

custom appears not to have been adopted by the Celts in Britain, and, where

found suggests Roman belief and practice (Black 1987).The lack of any trace

of coins at the Otford cemetery, although they occur nearby as field

scatter, reinforces the premise that the graves contain the mortal remains

of people adhering to local traditions, in line with Ross’s conclusion that

'with the imposition of Roman rule and the creation of the Civil Province of

Britain, the south soon settled down under Roman rule and the country people

no doubt continued to live in much the same way as before, with a nominal

respect for the gods of Rome and the dull divinised emperors', and a

continued veneration for the old, proven gods of their own tradition (Ross

1967).

A Celtic preoccupation with the human head is

undeniable, with numerous literary allusions to the miraculous survival of

severed heads, e.g. the legend of Bran the Blessed. (G. Jones & T. Jones

(trans.) 1974). Votive offerings of heads, both real and carved, have been

recovered from sacred sites throughout the Celtic world, and a stone doorway

excavated in Roquepertuse, Gaul, was decorated with relief stone-carved

heads interspersed with human skulls rebated into the stonework (Delaney

1986), thus demonstrating the intended visibility of such and thereby adding

weight to the observations made 'in Graeco-Roman literature (Green 1986).

There are ample indications that burial grounds were intended to be

continuing reminders to the living of those who had gone before, hence

cemeteries must have been demarcated in some enduring manner, with either

boundary ditch, posts, hedge, fence or wall. Walled cemeteries and funeral

monuments within walled enclosures are restricted almost entirely to the

South-east, with eight of the fourteen identified being in Kent (Jessup

1970), and the Otford cemetery was provided with one such monument, a

mausoleum, although limitations of excavation have not to date permitted a

search for a boundary. Nonetheless, the proximity to a contemporary trackway

strongly points to the need for some form of delimitation, perhaps a thorn

hedge, if only to keep out wandering cattle.

Personal

gravestones or markers may be expected in view of the fairly regular spacing

of the graves in most Roman burial grounds, strongly suggesting that

individual locations were marked for posterity; in no instance at Otford

were graves superimposed as would be likely if markers were absent. Indeed,

the presence of a 'stake-hole' within one of the urns (group 2) might

represent such a grave-marker, but could equally well date from any

subsequent date. However, a small post-hole close to an urn at St. Pancras

(group 146) contained a mass of charcoal which 'may have been the charred

base of a marker post’ (Down & Rule 1971) and the tentative identification

of a simple late-first century cremation grave at Eastwood, Fawkham, as

being marked by a stake (de la Bedoyere 1989), do reinforce the marker

theory. Also, one of the two grave groups at Canterbury castle had 'just to

the north, four tile fragments stacked one upon the other, possibly the base

of a grave marker', these graves being probable survivors from a larger

cremation cemetery destroyed during the building works of the 1950s (Bennett

et al 1982).

In addition to cemeteries, Britain has the

remnants of a number of upstanding Roman funerary monuments, the dating of

many of which is obscure. The most numerous class is the round barrow of

which some one hundred are known, and which has an antecedence stretching

back to the Neolithic period. It persisted through the Iron Age, notably in

the great round Belgic barrows at Lexden near Camulodunum, and occurs in

Roman Britain primarily in the South East, where circular conical barrows

are found singly and in groups, notably at Bartlow in Essex, where five

barrows contained wooden chests enclosing cremations and one covered a

tile-built burial cist (Toynbee 1971).

At Holborough near

Snodland, a barrow, known locally as Holborough Knob, containing a

particularly richly furnished cremation was excavated in 1954 in advance of

chalk quarrying. The bones were placed in a wooden coffin placed in a grave

over which a puddled chalk dome was erected initially, then enclosed in the

barrow-mound. The funeral pyre was elsewhere, from whence grave goods:

potsherds, fused glass, burnt bones including those of a (?) sacrificed

cockerel, a memorial coin to Antoninus Pius (died A.D.161) depicting a

funerary pyre, and the frame of an iron and bronze folding stool were

brought. The funeral ceremony is deemed to have been conducted from a

temporary shelter and included a libation of resinated wine. An unusual

feature is the insertion of a secondary, infant-female, inhumation with the

coffin decorated with Dyonysiac figures. Stylistically, this dates from the

early third century (Jessup 1955, 1970).

A round

barrow at Plaxtol, described as a large hillock with a covering shaw, some

28 ft. in diameter, containing a central inhumation and a number of

secondary Roman cremation groups around the circumference, was grubbed out

in the mid-nineteenth century. At the same time it was concluded that traces

of a foundation nearby represented a wall delineating the cemetery (Luard

1859).

A development of the 'earthen barrow' after the

Italian style, is the enclosure of the barrow within a low masonry drum. Of

this type is considered to be a round tomb at Keston with a 3 ft. wide flint

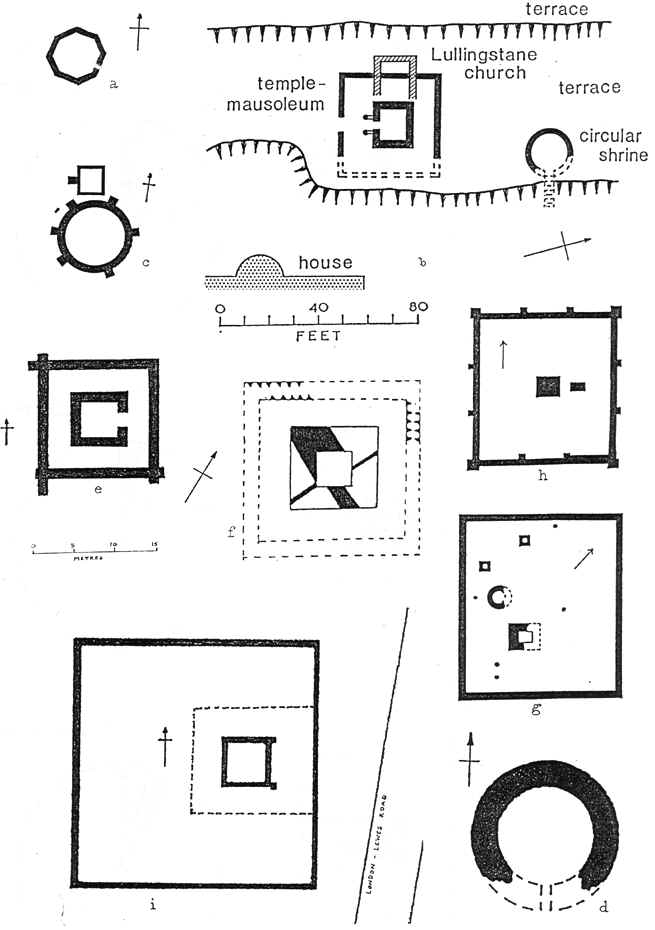

wall without an entrance, having six radiate external buttresses (Fig 2c),

which, besides resisting the outward thrust of the barrow, may have

supported low ornamental pillars (Toynbee 1971). Alongside this was a

rectangular tomb chamber containing a stone coffin (Detsicas 1983), and also

a cremation inside a rectangular lead casket within a tile tomb (Jessup

1970).

Figure 2 a) Otford

mausoleum, b) Lullingstone complex (after Meates 1979). c) Keston tumulus &

tomb.

d) Pulborough mausoleum ( after Collingwood & Richmond 1969). e)

Lancing Down temple (after Bedwin 1981).

f) Mausoleum Welwyn (after Rook

et al 1984). g) Langley walled cemetery. h) Springhead walled cemetery

(after Detsicas 1983) i) Titsey temple (after Graham 1936).

Introduction

To Frog Farm Cemetery contents page Frog Farm Site

This website is constructed by

enthusiastic amateurs. Any errors noticed by other researchers will be to

gratefully received

so that we can amend our pages to give as accurate a record as

possible. Please send details too localhistory@tedconnell.org.uk

|