|

Aspects of Kentish Local

History

|

Otford & District Archaeological Group (ODAG)

The

Romano-British Cremation Cemetery at Frog Farm, Otford, Kent, in the context

of contemporary funerary practices in South-East England by Clifford P. Ward

1990

Frog Farm Site, Otford

The importance of

the Pilgrims’ Way/North Downs Ridgeway is underlined by Margary

(1965) who commented that ‘this route is certainly one of the most

important prehistoric thoroughfares in the south-east of England,

for it was from the earliest times the main link between the

Continent and that central downland area of Wiltshire which played

such an important part in the settlements of early man in this

island’. The Darent crossing was one of only five river crossings

required between Folkestone, Farnham and Wiltshire. It comprised a

ridgeway and terraceway below the steep escarpment of the chalk

downs, and ‘formed a valuable link between various Roman sites at

the foot of the downs’. Thus, in the absence of any known east-west

Roman road through Kent south of Watling Street, it may be assumed

that the Pilgrims' Way formed a part of the main communications

network of southern Britain.

The geology of Frog Farm is dictated by the river Darent which in

its course to the Thames broke through the chalk North Downs at this

point. Underlying the chalk is a stratum of gault clay forming the

flat floor of the Vale of Holmesdale, while superimposed on this is

the alluvium of the river flood plain, considerably greater in

extent than befits the present water flow. The actual cemetery site

is on a spread of Second Terrace river gravel, and stands at O.D.

220 feet (Dines et al 1969).

At this point the Pilgrims' Way utilises a slight ridge to climb

westwards from the Darent crossing, and the cemetery would have been

visible from all directions. (map.)

Apart from a small group of Roman pots unearthed north-east of

the farm in 1906, and presented to Maidstone Museum (Acc. not

traced.), the first indication of Roman occupation of the area came

in 1927 when a contractor was laying a gas pipe beneath the Pilgrims

Way. A ‘very hard surface’ was encountered, which was identified, on

very dubious grounds, as a Roman road. The fact that the Sevenoaks

Council granted an additional £35 12s 6d to cut a trench through it

gives some indication of its strength and/or extent (G. Ward

c.1930), but unfortunately nothing further is known, despite a

watching brief kept on subsequent holes in the vicinity. Its

massiveness suggests a structure rather than a road, just possibly a

shrine or further mausoleum, or even the elusive villa long-sought

to the west of the river.

At about the same time a burial group, dated to the second

century A.D., was unearthed at Frog Farm, vessels from which are now

deposited in Sevenoaks Museum. (Acc. K1394).

The site of the settlement at Wickham Field, the former Isolation

Hospital, was subjected to trial excavation in the 1920s & 30s when

evidence of a settlement was found (Clarke & Stoyel 1975), and a

series of investigatory trenches was opened there by the

newly-formed Otford & District Historical Society Archaeological

Group (ODAG) in 1965.

At the end of that year, during construction of a shallow

drainage trench for a potato-clamp immediately outside the back

garden of Frog Farmhouse, a group of Roman pots was discovered by

the farmers, and ODAG was invited to investigate. This group was

identified as a cremation burial group (Grave 1), and in another

part of the trench a substantial ragstone wall was noted which

exhibited a 45° corner and was pierced by a somewhat enigmatic flue.

This subsequently proved to be the best-preserved portion of an

octagonal mausoleum (see below).

In view of the shallowness of the grave bottom, about 16 inches

below the surface, there was a strong possibility that any further

disturbance of the site would cause serious damage to any other

artefacts nearby, and, with the encouragement of the Booker family,

the farmers, a decision was taken to excavate the site in order to

rescue any other remains which might have survived, and to endeavour

to trace the angular building which disappeared beneath a manure

heap.

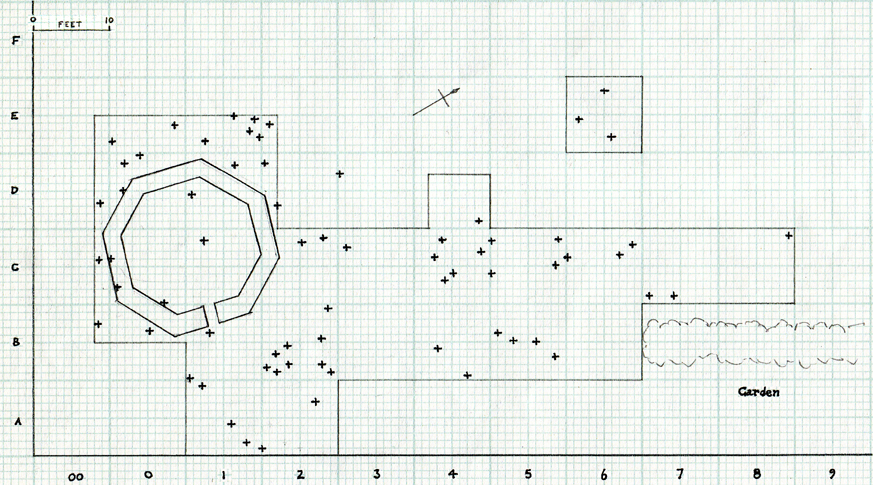

A 10 feet by 10 feet grid was constructed aligned on the adjacent

garden boundary (a gooseberry hedge) and work proceeded over the

next two years. Due to farming needs it was not possible to extend

the grid northwards or westwards apart from in one area (E 6), and

the garden precluded any extension to the south, although the hedge

was curtailed slightly (See Plate 1).

Plate 1. Frog Farm Cremation Cemetery and

Mausoleum - Schematic Plan

Over the area

excavated a series of grave-groups was located immediately beneath

the plough level, mainly in shallow, ill-defined scoops in the

underlying brickearth, and from the damage occurring to all of the

larger vessels, it appeared that the ground surface had been lowered

by up to 1½ feet since the cemetery was in use.

Although no regular pattern of deposition could be ascertained,

unlike the "lines" suggested at e.g. Borough Green (G. Payne 1899)

and other places, the groups were generally spaced at 3-5 feet

between centres, with, in only two instances (Groups 7 & 57),

suggestion of two urns buried together.

The urns had all been placed in holes dug into the gravel

sub-soil, at least three being lined with flints. They were set in

an upright position with ancillary vessels, where present, grouped

round them, having in 8 instances a platter used as a lid to seal

the mouth of the urn. In one case only (Group 18) two fragments of

roof-tile (tegula) had been added to the plate, presumably to

enhance the effect.

The damage to the urns in particular, indicated that they had not

been buried deeply, as many of the vessels had been crushed, with

their rims having fallen on to the bones, leaving the upper portion

of the walls upstanding. In many cases these had been ploughed off

subsequently, rendering complete restoration impossible, but

retaining the most significant identification features i.e. the rim

types together with reasonable indications of the overall size and

character of the vessels. Some of the urns, however, had been

virtually ploughed out, leaving only the base in situ. All were

invaded by grass and other roots, and many were badly distorted.

Some attempt at analysis of the composition of the grave-groups

has been made (Figs

3-9), but there is little indication of strong trends in either

pottery associations or dating in different areas of the cemetery,

although Patchgrove urns preponderate, and of ancillary vessels,

Samian appears to form a higher than usual proportion.

The majority of the samian ware has been identified and dated

from 150-200 A.D. In common with most others the cemetery does not

contain any decorated samian ware, which suggests that it was deemed

unsuitable for funerary purposes. The predominant form is the

platter (Dr 18/31 etc), of which there are 26, with cups (Dr 33

only) numbering 17 (see analyses below).

The piece de resistance came from Grave 45 where a two-handled

samian cup of rare form imitating a metal vessel was placed within a

greyware pie-dish, and had a small samian dish (Dr 36) over it. The

cup was submitted to Dr Grace Simpson who appraised it as Dr 34

having both body and slip of clays containing very fine mica, as

found at Lezoux. The slip is black, through a reduction process in

firing. The vessel is dated A.D. 138-180. Of the original two

handles, one had become detached prior to burial and the scar

appears to have been deliberately smoothed off to some extent, end

it is tempting to think of the cup as perhaps rejected after

accidental damage in a nearby villa, and rescued for use by one of

the local peasants, for whom it became a favourite drinking vessel,

and ultimately accompanied him to the grave.

Towards the north-east, the burials were further apart, shallower

and more fragmentary. It appears that the land surface had been

subject to greater erosion, presumably through ploughing, although

at slightly lower elevation than the mausoleum. The absence of any

remains whatsoever in Grid B6 may indicate the extent of the

cemetery on the eastern side, although no trace of any boundary was

encountered.

In view of impending changes in agricultural operations it was

decided to conclude the excavation by attempting to recover the plan

of the building which until then lay beneath the manure heap. This

was accomplished over the last weekend of April 1968 (plan) and

immediately backfilled. Due to the arrival at that time of the

writer’s baby daughter, the overall appearance of the mausoleum is

known only from photographs (Plates 3, 4 ) and thus some of the

details, e.g. the existence of two small pieces of lead, suggestive

of coffin sheeting of Keston, (not preserved among the finds), said

found in a slight depression at its centre cannot be attested by the

writer.

Plate 3. Frog Farm, Otford. Mausoleum from the

south-south-east with entrance on right.

Plate 4. Frog Farm, Otford. Mausoleum from

the west-south-west showing badly robbed

foundations and earlier cremation graves in situ in foreground and to the right.

The structure was

found to be badly robbed over most of its circumference, with only that

portion adjacent to the entrance standing above the foundation which was

composed of 2 courses of flint nodules bedded in gravel 36 inches wide. It

was octagonal in plan with an entrance only 20 inches wide in the centre of

the east-south-east face. Above the flints was one course of neatly-laid

faced ragstone blocks set in

white mortar. These formed walls 34 inches wide. The wall/foundation

did not continue below the entrance, which had been used at some

time, apparently late in the Roman period, as a flue.

The comprehensive robbing had removed all traces of floor and

superstructure beyond a few small opus signinum and tile, both

tegula and imbrex, fragments. No indications of postholes or sleeper

beam slots were noted in the ragstone wall, but the insubstantial

nature of the foundations suggests that the superstructure was

either timber-framed, or, if stone built, limited to one storey.

Nothing can be adduced about the roof, but the few tile remains

point to a tile cladding rather than thatch, and the ragstone for at

least the lower courses of the walls must have been transported a

minimum of two miles from the lower greensand ridge to the South,

suggesting a building aspiring to some degree of ostentation. ODAG's

identification of the structure as a mausoleum was confirmed by the Museum

of London (N.C. Cook pers. discussion).

[NB by adding in the additional groups found in 2006, and the

subsequent Nil groups west of the N-S track to the fields, it should

be possible to make a better guestionmate of the likely size of the

cemetery - perhaps as a Supplement to include the commercial

archaeological contractors work and ODAG's own. We came to the

conclusion we did not want any more, provided they were not under

threat!]

Funerary Practices To Frog Farm Cemetery

contents page Discussion

This website is constructed by

enthusiastic amateurs. Any errors noticed by other researchers will be to

gratefully received

so that we can amend our pages to give as accurate a record as

possible. Please send details too localhistory@tedconnell.org.uk

|